5 Minute Read

Share this article…

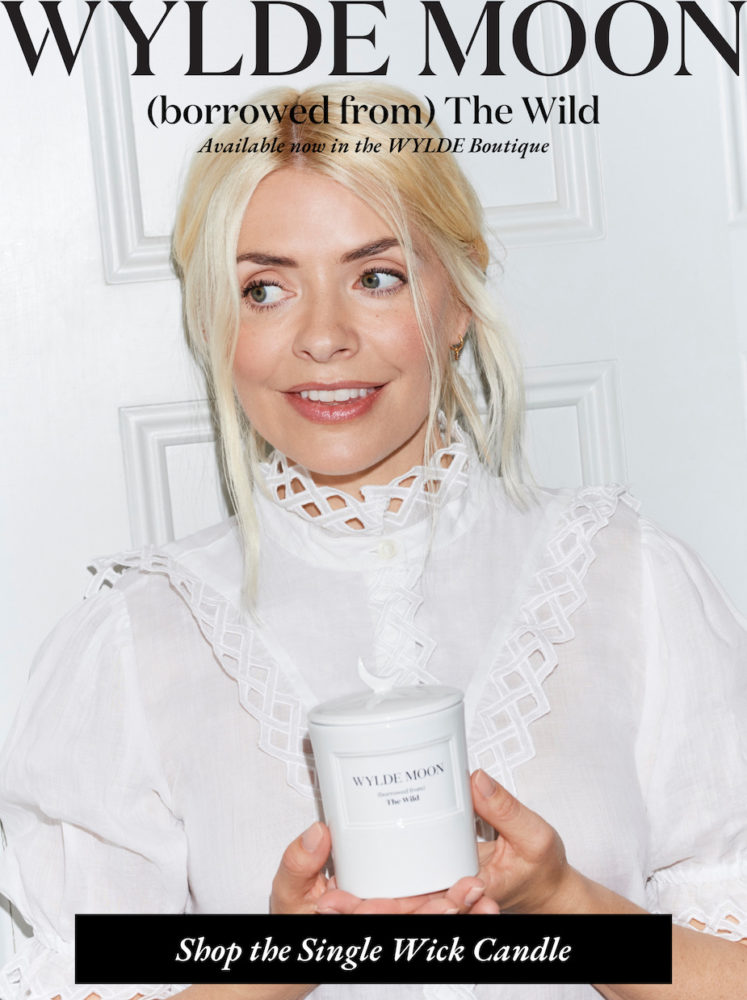

Jill Allen-King at the Pride of Britain Awards

Holly was blown away hearing Jill Allen-King’s story at the Pride of Britain awards and felt without doubt she was a WYLDE Woman, offering inspiration in the toughest of times.

Despite the unimaginable trauma of suddenly losing her sight, Jill Allen-King, 82, from Essex, has dedicated her life to making the world a more welcoming place for blind and partially sighted people

As a baby, Jill contracted measles, which attacked her optic nerve and led to the loss of one eye. With 80 per cent vision in the remaining eye, she was able to lead a full and happy life until, in a tragic turn of events, Jill suddenly suffered a glaucoma attack on her wedding day in 1964 and lost her remaining sight.

“I wish that I had seen myself dressed as a bride,” says Jill. “My dressing table had already been moved from my bedroom to our new house and I never got a chance to see myself in any of the photographs.”

Jill went on to have a baby the following year but she spent her daughter’s early life too scared to go out alone. Thankfully, everything changed when she got her first guide dog, Topsy, in 1971. Finally able to venture out with confidence, she was shocked by how few places allowed guide dogs and began campaigning for better access to libraries, restaurants and public spaces. Tireless campaigning and fundraising earned her an MBE in 1983, an OBE in 2011 and this year, Jill won the lifetime achievement award at the 2022 Pride of Britain awards. “The rights of blind people are continuing to not be considered, so I will keep working to fight that,” says Jill.

What do you remember of your wedding day?

What do you remember of your wedding day?

“My vision had started to go blurry the night before but the doctor said it was probably just nerves. On the morning of the wedding, I caught the bus to the hairdressers and got dressed back at home, in my mum and dad’s house. As I walked down the path of our cottage to head for the church, a black cat crossed my path and I remember thinking, ‘That’s bad luck.’

We had the ceremony and I signed the register – the last thing I ever wrote with my sight. But when we reached the hotel for our reception, I was walking down the long corridor to the banqueting suite and it seemed like the lights were flashing. I whispered to my husband Mick, ‘My vision is going funny, but don’t tell anyone.’ Shortly after that, we were shaking hands with all our guests when a terrible pain started above my eye. I felt terribly sick and scared. I don’t remember eating the meal but somehow I made it through our first dance – the waltz.”

So you just carried on?

So you just carried on?

“Yes – I didn’t want to spoil the day. When we left for our honeymoon in Eastbourne, I remember standing in Victoria station and feeling panicked. We made it to the hotel but Mick decided to call a doctor who took one look at me and sent for an ambulance. I still had confetti in my hair when I reached the hospital. It turned out to be glaucoma, linked to the original damage to my optic nerve. I was moved to Southend for an operation but my sight couldn’t be saved – with glaucoma, you really need to be treated as quickly as possible.”

Do you remember the last thing you saw?

Do you remember the last thing you saw?

“I remember my dad’s friend leaning into the wedding car and taking a picture of us on our way from the church to the reception. I never got to see the photo though.”

How did you come to terms with it?

How did you come to terms with it?

“I don’t think you ever do – you just learn to live with it. I lost everything. In the beginning, I felt angry – I used to think, ‘Why has God done this to me? I’ve always tried to do the right thing.’ But as the years have passed and I’ve met so many people with different disabilities, I’ve learned that this is God’s way of using me to help other people.”

What were the early years like?

What were the early years like?

“Being partially sighted and being completely blind are like two different worlds. It’s very sad because I’ve never seen my daughter, my grandchildren or even my second husband, Alvin.

Before it happened, I loved ballroom and latin dancing, and I used to catch the train to London every day to do my job as a chef. But when I went blind, I couldn’t do any of that. I was practically housebound.

I was blessed with a daughter a year after we married and that gave me something to live for. In those days, lots of doctors didn’t believe blind people shouldn’t have children and after my daughter was born, I was persuaded that sterilisation was the best thing for me. Going through with that is my only regret in life.”

“My father used to say to me whatever you want to do you will do well. It was great advice. You must take knocks in life and learn from them, to be better.”

How did you cope?

How did you cope?

“In the first few years, I was determined to prove that a blind person could and should bring up a child. I was completely focused on being a good mum – the best I could be. I wanted to read to Jacqueline so that inspired me to learn Braille.

When she was about three, I started doing some radio recordings for the BBC about our life together but it was very limited because I couldn’t leave the house by myself. Then in 1971, I got my first guide dog. I was thrilled to bits and on our first day, I set off with Topsy to take Jacqueline to the library. However, when we got there, I was told I had to wait outside with Topsy. I felt so angry and upset, and Jacqueline cried all the way home. That was the first time I thought, ‘This isn’t right’ and from then on, I just kept fighting.”

How did you keep going?

How did you keep going?

“Progress was very gradual. I wrote letters to the House of Commons for 12 years just to be allowed access to the public gallery. Even in 1983, when I got my MBE for my guide dog access campaigns, Brandy wasn’t allowed into the ceremony at the palace. “

Jill Allen-King with her guide dog

What’s been your proudest achievement?

What’s been your proudest achievement?

“That’s a difficult one! I came up with the idea for passwords so that when utility companies send someone to your door to read the meter, they have to know your password to prove their identity. It can be very frightening to open the door to a stranger so I’m proud of that. But then I also came up with the idea for textured pavements at road crossings – we got the first one laid at the House of Commons in 1982. They’ve helped blind and partially sighted people feel so much more confident about going out.”

You sound like you’re still as busy as ever…

You sound like you’re still as busy as ever…

“I am. In my free time, I knit muffs for dementia patients. They’re tactile muffs so that people with dementia can put their hands in and fiddle with them. When I lost my sight, I never stopped sewing or knitting and I actually found that I was better at knitting when I became totally blind. I used to drop stitches when I could see!”

What advice would you give to anyone reading this?

What advice would you give to anyone reading this?

“Treat every day as a special day because tomorrow might never come.”

Jill has written two books. “Just Jill” and “Jill’s Leading Ladies”, both published by Apex and available through Amazon.

Follow the official WYLDE MOON accounts on Instagram, Facebook and TikTok, and sign up here for exclusive content from WYLDE MOON and Holly Willoughby.

Share this article…